Founding History

In Oakland, Mr. Morrow called on the Parker-Goddard Secretarial School. Presuming men ran the business, Morrow found to his surprise that the school was owned by Miss Mabel Parker and Mrs. Adelaide Goddard, and not by men at all. As Morrow explained his mistake and was about to leave, Mrs. Goddard remarked “When the men admit women as members of their service clubs, I would be interested”. This remark sparked an idea for the entrepreneurial Mr. Morrow, and he got together several of the outstanding businesswomen in Oakland to pursue the idea of forming a service club for women.The preliminary meeting was held Tuesday, May 31, 1921, at 4 p.m., in the Rose Room of Hotel Oakland. Of the six women in attendance only one, Adelaide Goddard, is recorded as showing real interest. Undeterred, Mrs. Goddard immediately began recruiting her acquaintances. Less than a month later, on June 21, the historic First Meeting of Members Committee Luncheon, comprised of 10 women, met at the Hotel Oakland to officially launch the club. The core group met once a week, and in three short months they had gathered the support of 80 women in Alameda County, the number stipulated by Mr. Morrow as minimum to form a charter club. The group also chose the name Soroptimist for the organization at this time, which historical Soroptimist records list as a word coined from the Latin “soror”meaning sister and “optima” meaning best, which was interpreted as The Best of Women. In current usage Soroptimist is interpreted as Best for Women. This change shifted the focus away from the early qualifications for Soroptimist membership to the lives of the women and girls whose betterment is the worldwide Soroptimist mission.

The Articles of Incorporation of this first county-named Soroptimist Club of Alameda, were filed and signed by Stuart Morrow in Sacramento, September 26, 1921. The charter contains the names of the first club officers: President-Violet Richardson; Treasurer-Nellie M. Drake; Directors-Edna B. Kincaid, Doris C. Tilton, Gladys R. Leggett, Blanche Rollar and Adelaide Goddard. At the bottom of the document are the names of the 80 professional women required to file the charter. Significantly, the charter designated that additional clubs would be founded and operated throughout the United States, with the principal business of ALL clubs transacted in Oakland. This immediately set the precedent for an arm of control and cohesion as the organization grew, represented today by Soroptimist International, Inc. located in Cambridge, UK.The presentation of the Charter and the officer installation ceremony took place in formal style at the Hotel Oakland a week later, on October 3, 1921. This installation date, October 3, is officially celebrated as Soroptimist Founders Day.

The real significance of this first-ever women’s service club may today be underappreciated, but at the time it was revolutionary. By the beginning of the 1920s women in North America had established themselves in the political arena through suffrage, and in the professional world as a result of World War I. But the idea of a service club exclusively for women was unheard of. Thus with the advent of this first Soroptimist club a major social divide had been bridged.One of the most notable facts about the charter is that Mr. Morrow was the only signer. History also records that Mr. Morrow named himself as originator, founder and general manager of the corporation, retaining 90% of the voting power, property rights, and interest in the corporation. In other words, he owned Soroptimist. This, of course, had to change.SOROPTIMIST FOUNDING HISTORY

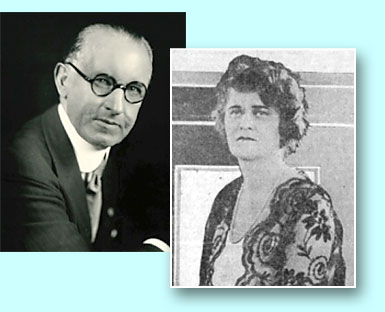

Charter Member, Founder/President Violet Richardson. An attendee at the First Meeting of Members Committee Luncheon, Violet accepted the Presidency only on the condition that the Soroptimist Organization be international in scope.

Attorney Eloise B. Cushing, major writer of the first Constitution and By-Laws. These were required for the filing of the Charter, and they subsequently served as guidelines for all national and international clubs. Cushing was a life-long Soroptimist, and one of Violet’s closest and longest-lived friends.

Helena M. Gamble, the first Soroptimist club secretary, who later became Historian for Life for her meticulous collection of early records and photographs. Soroptimists owe much of our early written history to this lady, including reports of the many problems, disputes, pleasures and accomplishments of the early Soroptimist clubs.

Following the organizing of this first, county-named Soroptimist Alameda Club, Mr. Morrow began to fulfill the vision of an international Soroptimist organization. He started, however, by chartering three additional important and influential national clubs in 1922: San Francisco on March 6, Los Angeles on July 19, and Washington, D.C. on November 27. This accomplished, the enterprising Mr. Morrow, who was familiar with Great Britain and Europe from having promoted Rotary Clubs there some years earlier, crossed the Atlantic. In England he organized the Greater London Club in 1923, with Kathleen, Vicountess Falmouth as Founder President and 112 Charter members. The London Club installation was reported to be the social event of the season, attended by 250 people, including members of the British Royal family.

Kathleen, Vicountess FalwellCharter PresidentSoroptimist Club of London

Dr. Suzanne NoelCharter PresidentSoroptimist Club of Paris

In 1924 Mr. Morrow went on to Europe, and organized the Soroptimist Club of Paris. The Founding President there was Dr. Suzanne Noel, who later went on to become the first President of the European Federation.At this point the existing clubs had charters, but they did not own their organization. This untenable situation could not stand, and in 1927, just six years after the Alameda founding club was chartered, Morrow agreed to sell all rights, title and interest in the name Soroptimist, and all rights in the corporation for $5,500. Eight clubs cooperated to underwrite the purchase, including clubs in Great Britain and Europe. The $5,500 purchase price may sound reasonable or even a bargain today, but this was 1927, and women were not making significant salaries. The world was still reeling from World War I (1914-18), the 1919 pandemic influenza epidemic that killed between 20 and 40 million people worldwide, and the U.S. was gripped by the wild stock market gyrations that two years later, in 1929, would result in the Great Depression. Times were anything but perfect for acquisition. But early Soroptimists worldwide recognized the pressing need to control their organization, and all contributed to the purchase price in spite of these catastrophic events. From this point forward Soroptimist showed steady and determined growth towards the emulated global organization it has become today.

Another noteworthy historic event took place in 1927, when the First World Conference of Soroptimist Clubs was held in Washington, DC. At this conference the American (SIA) and European (SIE) Federations were formed, as was Soroptimist International (SI), to provide the essential link between all present and future clubs. Other significant milestones at this conference were the decision that Soroptimist International Conventions be held every four years, and adoption of the Soroptimist emblem for the member pin. Designed by Anita Houtz Thompson of the Oakland Club, the original casting of the pin is today on display at SIA Federation headquarters in Philadelphia, PA. In subsequent years the design has been changed a number of times, in an attempt to reflect international as well as developed country’s women’s attire.Soroptimist continued its Federation growth when in 1934, eleven years after the first world convention; Great Britain and Ireland broke away from SI Europe to form the Federation of Great Britain and Ireland (SIGBI). Another forty-three years were to pass before 1978, and the founding of The Federation of the South West Pacific (SISWP), with Mary Whitehead as its First President. And with this addition the current four SI Federations were complete.In 1978 a major structural change was made in SIA Federation’s Pacific Region, to which SISD belonged. With 168 clubs, this Region was the Federation’s largest, and it was decided to divide it into three Regions, which were named Desert Coast (DCR), Golden West (GWR), and Camino Real (CRR). The Desert Coast Region, to which SI San Diego now belongs, was further divided into 3 Districts, with SISD in District III. The Desert Coast Region today remains one of the largest in SIA, consisting of approximately 1400 members in 47 clubs.

VIOLET RICHARDSON

Violet Richardson was not just ‘another woman’ of the club in the founding years of Soroptimist. She was an early and determined feminist and an innovator in the Physical Education field for women. So, a more in-depth review of the highlights of her life is in order. To Soroptimist member and friend of Violet’s, Lillian Estelle Fisher, much credit is due for what we know of Violet’s personal and professional life. This was recorded in Miss Fisher’s 1983 biography: Violet Richardson Ward, Founder-President of Soroptimist.Violet was born in Summit, New Jersey on August 27, 1888, the third child and second daughter of John Mead Richardson and Lucie Shipgood Richardson, who had emigrated just three years earlier, in 1885, from Great Britain. Violet’s parents were unusual for a couple in late 19th and early 20th century United Kingdom. Both had been active in the care of the poor, ill and homeless with William Booth in London, when Booth founded the Salvation Army. This is where John and Lucie actually met. They were an emancipated couple who had total respect for each other, and a lifelong concern for those less fortunate. Lucie was extensively self-educated, and John, whose education was supported by his winning many scholarships, held responsible positions in early telegraphic work.The Richardson’s immigration to the U.S. started on an impulse, when John and Lucie walked along a dock in France at the start of a three-week vacation there in 1885. Lucie’s parents had immigrated to Australia, and they inquired if the ship about to depart was going there. On being told it was about to leave for America, and determining that they could afford the lowest class return ticket price, they packed up their two children and decided to visit America instead. The ship docked in New York where, two days later, John declared that they must stay in America, with the understatement that it was too big to see in three weeks. Another factor was surely that he was violently seasick throughout the entire trip, a limiting factor that would give anyone anticipating a return Atlantic crossing pause. He reportedly never set foot on a ship again in his life. Immigration in those days was undisciplined, people simply came and settled. John soon found work, and was for most of his American career employed by the railroads, which furthered his intent to take his family to see the country.Violet’s early experiences with her energetic parents were noteworthy. At the age of 10 she and her mother traveled by ship to London to visit relatives there, where Violet thought the fine clothes and top hats of the gentlemen were ridiculous. At the age of 12 she went to Mexico City for a week with her father, who had railroad business there, and met President Diaz. She loved Mexico, visiting her first orange groves, volcanoes and mountains, and generally made the best of her week-long stay. Also at the age of 12 her father took her to Washington, DC to see President McKinley inaugurated, and then deliberately took her to the slums in the side streets surrounding the Capitol buildings to broaden her perspective. She could hardly believe such conditions could exist in America. In everyday life Violet’s parents were equally unique: a parade of unknown but interesting guests were frequently invited to dinner by her father or mother, providing non-stop intellectual stimulation for the entire family. John Richardson took his family to a Methodist Church and, dressed like a proper English gentleman, sat always in the front row. But if the sermon did not please him, he stood up and he and the family left. Through his work on the railways John set up free day trips on holidays for the underprivileged. Their house was always full of pets, cats in particular, and Violet had a horse to ride to school, thus distinguishing herself very early from the norm. She continued riding throughout her life.All three of the Richardson children were bright, but Violet clearly had a persistent streak that was unmatched by her elder siblings, Daisy and Stanley, to whom she was totally devoted, as were they to her, calling her Babe. The family relocated several times on the east coast before 1907, when they moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. Violet was 19, and after finishing high school she enrolled at the University of California in Berkeley as an art major because she had earlier won an art contest. However, she soon realized that her passion was in health and physical education, and she changed her major. In 1911, while still a student at the University, she organized the Berkeley Women’s Gymnasium, shocking the local populace by allowing her students to wear bloomers while exercising or playing basketball, unheard of before that time. One year later, in 1912, she received her baccalaureate degree in Physical Culture.All three of the Richardson children were bright, but Violet clearly had a persistent streak that was unmatched by her elder siblings, Daisy and Stanley, to whom she was totally devoted, as were they to her, calling her Babe. The family relocated several times on the east coast before 1907, when they moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. Violet was 19, and after finishing high school she enrolled at the University of California in Berkeley as an art major because she had earlier won an art contest. However, she soon realized that her passion was in health and physical education, and she changed her major. In 1911, while still a student at the University, she organized the Berkeley Women’s Gymnasium, shocking the local populace by allowing her students to wear bloomers while exercising or playing basketball, unheard of before that time. One year later, in 1912, she received her baccalaureate degree in Physical Culture.While in her second year of study at the University Violet had also begun to teach physical education classes to the underclassmen, and in addition substituted in the physical education departments at Mills and Holy Names Colleges in nearby Oakland. On discovering that she was being paid only $20 a month by the University when the man who was merely taking attendance was paid $40 per month, she insisted on equal pay, and when she was refused, she quit. The University President rehired her at $40, but raised the man’s salary to $60, so she quit again, and did not return to teaching until the University Board of Regents signed an employment contract which guaranteed her an equal salary each month. Many such instances of Violet standing up to or simply ignoring the status quo to protest inequalities or to implement her ideas are recorded in Miss Fisher’s biography.In 1914 her father decided that Violet should have a car to help her in her work. So she became one of the earliest car owners in the Oakland area. Two years later in1916 Violet received her Master’s Degree from the University, and was hired by the Berkeley School District as Supervisor of Health and Physical Education for the District. She established physical education classes for boys and girls in grade schools, and established the first physical education classes for girls at Berkeley High School. During her later career Violet also served as Director of Physical Education for the entire Berkeley School District.In addition to her educational work Violet wrote Sunday supplements for The San Francisco Chronicle, The Oakland Gazette and The Berkeley Gazette, for which she received no writing credit. But she allowed this because she felt that getting her opinion out on issues of importance to her would do some good for the causes she espoused. There seemed never to be an issue involving women, physical education or civil rights in the Bay Area that she did not actively participate in, and frequently lead. Violet was quite tall and her stature, added to her forceful personality, resulted in her having considerable influence in all causes to which she was attracted.

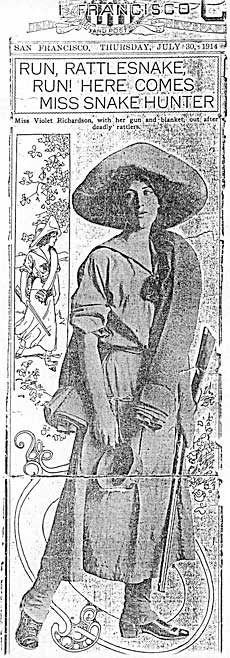

On July 30, 1914, Violet was profiled in the San Francisco Chronicle and Post newspaper as “Miss Snake Hunter”. She had organized a Women’s Hiking Club so that women could enjoy the pleasures of the Berkeley hills on Sundays and holidays, and she hiked with a shotgun in hand because of rattlesnakes in the hills. She was 26 years old, clearly already a woman people were noticing.So, it was obvious seven years later, in 1921, when Mr. Morrow arrived on the scene in Oakland, that Violet would be one of the first women approached about the new women’s organization. She was now 33 years old, and at the time deeply grieving the death a few months earlier of her beloved father, John, yet she was one of the first ten women who met to found the club. Violet herself liked to tell the story that when it came time to vote for Club President so many of her former students were members and voting for her, that she broke a tie on the third ballot by voting for herself. Good choice, because Violet, as might be expected, hit the ground running. In spite of the promise of Soroptimist being a club dedicated to service, when first getting organized the Soroptimists also met as a luncheon or friendship club. But not for long. Violet insisted that members be on time for meetings, and that meetings end on time. Her goal of service was put into action immediately. In their first calendar year of only three months Violet’s first President’s Report lists the projects for the year as installation of a heating plant for a Rescue Home, and care of three destitute families at Christmas.And so it went. As the clubs grew in the Bay Area and beyond, Violet remained active in as many of them as she could. As one of the first car owners in the Oakland area, naturally anything to do with driving conditions was of particular interest. In 1932 the Berkeley Club set up the first driving school in their city. They also insisted on having white centerlines painted on highways, for obvious safety reasons. In 1932 the club also proposed a fingerprinting plan for the police department, and contributed money to launch this plan. The club members, appropriately, were the first people to be fingerprinted when the plan was adopted. A later civic project in which the club participated was the “Save The Redwoods” campaign. The club raised $5,000, which when matched by the state of California, resulted in the purchase and preservation of a grove containing 7,600,000 feet of old grove redwoods, and 30,000 feet of fir trees. This was dedicated as the Soroptimist Grove on August 14, 1949. So it was clear that early Soroptimist activity overflowed regularly into civic issues and projects.

Violet’s non-profit work over the years took her widely beyond her Soroptimist activities and duties. She served twice as President of the local PTA chapter, not initially as a parent, but as a teacher. She taught American Red Cross water safety classes, was a member of the Kensington Girl Scout Council, the Order of the Eastern Star, the American Association of University Women, the YMCA, the University of California Faculty Club, the Berkeley Teachers’ Association and the Association of California Retired Teachers.Later, when Violet had to drop out of several organizations because she was so impossibly busy, her mother urged her stay with Soroptimist because, Lucie is quoted as saying, “There you shall be able to sit between a Catholic and a Jew, and this will be a broadening influence; make friends of other women in addition to educators, artists, physicians, lawyers and women of all kinds of occupations, then you shall learn a lot that can be applied to your own occupation”. These comments are illustrative of the ongoing influence of Violet’s mother, Lucie, in her life. Her parents were the role models that Violet emulated always.It was at a meeting of the Eastern Star in 1926 at the age of 38 that Violet met her future husband, Stanley Arthur Ward. On arriving at the Richardson home for their first date, Stanley discovered that Violet had forgotten all about it, and was out at one of her functions. Undeterred, Stanley made himself at home and spent the evening talking with Violet’s mother. He clearly made an impression, for when Violet arrived home after Stanley had given up and left, her mother told her “You better marry that man”. And she did marry Stanley that same year, referring to him always as her “friend-husband”. The wedding was at midnight because Violet was working, and only Stanley and Violet’s mothers were in attendance. It was held in Mrs. Richardson’s beautiful garden, which after Lucie’s death became Violet and Stanley’s, used throughout their lives incessantly for events associated with their combined organizational work. The newlyweds moved in to live with Lucie after the wedding, and never left this family home.Stanley was self-educated. He had never gone to high school due to the constraint of needing to work to support his mother and sister when his father deserted the family. Even without a high school diploma he ultimately challenged and was admitted to the University of California where he graduated, after which he went to Stanford to obtain his Masters degree. Stanley’s career was in what we today call vocational education, and he was one of five teachers who founded the Central Trade School in Oakland, which later became Laney College. Stanley had served in World War I, and was later in charge of a fleet of small airplanes. Shortly before Pearl Harbor he was made a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. navy. Then he was transferred to head the Aviation Metalsmith School in Jacksonville, Florida throughout World War II. Later he headed the Aviation Radio and Radar Schools there, until reassigned to head the special Aviation Radio and Radar School on San Clemente Island, just off the California Coast. At this point his and Violet’s wartime geographic separation was somewhat ameliorated, as he was frequently able to fly from San Clemente Island to Oakland to see her.Back now to December 18th, 1927, when Violet gave birth to her only child, her son, John, named after his grandfather Richardson. Since Violet and Stanley lived with Mrs. Richardson she took care of the baby, while they continued with their respective jobs and organizational activities. They were unable to have more children, which distressed them greatly, and adoption was denied because although they owned property they did not qualify financially. But John had plenty of cousins as he grew up and was never lonely.Thus their busy lives continued in the ensuing years as they remained active in both their work and their civic activities. Violet received many accolades from Soroptimist during her lifetime, and remained active into her late 80s. She retired from teaching and administration after 41 years and with Stanley, who had retired earlier, they began the extensive travel that characterized their later years. Getting a passport proved extremely difficult for Violet, because no public records could be found documenting her birth. She finally obtained a passport as Stanley’s wife, and they were on their way. Wherever they traveled Violet got in touch with and visited as many Soroptimist clubs as she could.

In the meantime their son, John, had married and had two children. Then, following a divorce from his first wife, John married a woman with four children from her previous marriage, bringing their offspring total to six. Violet treated all of them as her own and was totally involved in their lives, and they in hers, until her death, when yet another generation had arrived on the scene. Violet and Stanley’s love of the outdoors took them often to the major California parks with their grandchildren. In their later years when they traveled less, their home and garden was the scene of endless parties for visiting family members and the organizations in which they remained active.In 1971, the Fiftieth Anniversary of Soroptimist, the Golden Jubilee was celebrated. Violet, now aged 83, Stanley, and granddaughter, Sandra, traveled to Rome for the International Convention, where she was accorded the recognition she so justly deserved. Soroptimists from all over the world were thrilled at the opportunity to meet her. She was given an engraved silver tray on the occasion that she reportedly treasured throughout the balance of her life.

On their way home Violet and Sandra attended Queen Elizabeth II’s Garden Party at Buckingham Palace in London, excited by the event and meeting the Queen, but disappointed that Stanley did not have an invitation and could not attend. Back home in Oakland there were also major Fiftieth Anniversary events. Violet had a giant Redwood tree in the Soroptimist Grove of Humboldt County in northern California named “Violet Richardson Ward” after her, as a living memorial to her contributions. SIA Southwestern Region further celebrated the anniversary at Goodman Hall in Jack London Square in Oakland, “The Pilgrimage to Oakland – Where It All Began In 1921”. A bronze bust/portrait of Violet was dedicated at the event, which now resides proudly in the Oakland Library. Over 1000 Soroptimists from around the world attended the celebration.

Stanley’s death three years later on February 8, 1974, was devastating for Violet. She was 86, still active after two hip replacements, still driving her own car, and as mentally alert as she had always been. But she was getting old, and other friends were dying. The death of her life-long Soroptimist friend Eloise Cushing on July 6, 1977, at the age of 89 was another crushing loss. Violet herself never paid any attention to her age, and is recorded as saying on one occasion “They tell me I’m 92, so I guess I am”. But she did not live to be 92. Her memory was fading, and her health deteriorating. She was still living in her own home with grandchildren, great grandchildren and friends visiting frequently, and as much help as she needed to remain on her own. But by July 1978 her son, John, took her to his home in Danville, California, where she could have constant care. She died less than a month later, at 6 a.m. August 2, just twenty-five days short of her ninety-first birthday.